Written by Ephraim Zachary Heiliczer

Initial patent applications for startup companies often present unique challenges in maximizing patent protection while minimizing costs. In some industries, obtaining fast patent protection is vital for a startup to prove the worth of the technology underlying the startup. As explained below the following strategy is often most preferable for startup companies.

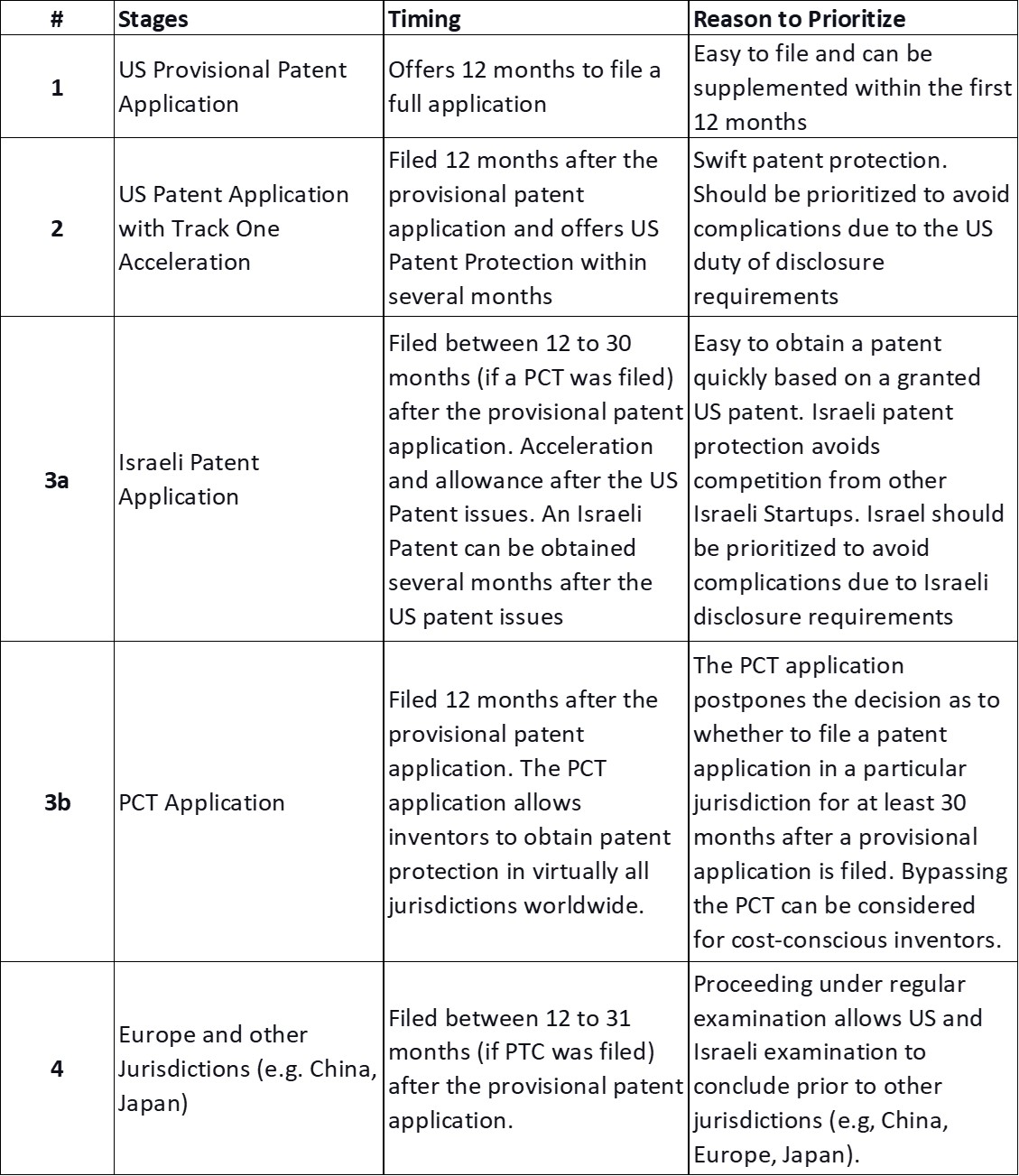

Patent applicants usually begin with a provisional US patent application. The provisional application offers a one-year period during which the inventors in the startup can continue researching and supplementing the application. The best path for a startup is often filing a regular US patent application after one year (or earlier, if desired) and accelerating its examination by filing a request for a track one accelerated examination process. Under the Track-one process, the USPTO will examine the application twice (if needed) in the first year. Patent applications examined under the Track-one process are often granted within several months, providing a fast avenue to prove the startup’s worth.

While filing a PCT application is best practice for most inventors, bypassing the PCT can be considered for cost-conscious inventors.[1] Israeli startups often consider Israel, Europe, China, and Japan as additional jurisdictions for patent protection.

Although Israel can be considered secondary in the minds of some startups, Israeli patent protection can be very important for Israeli startups. This is because innovation tends to occur in clusters, and patent protection can prevent competition with future Israeli startups. After obtaining a patent under track one in the US, Israel should often be prioritized as the second jurisdiction in which to obtain patent protection. The main reason is that Israel offers a quick and easy process for obtaining a patent by petitioning for allowance based on the granted US patent.

Another reason to prioritize the US and Israel over other jurisdictions is the duty of disclosure. The duty of disclosure, a primary issue in the US and Israel, requires applicants to disclose publications relevant to the examination of the patent application (e.g. novelty, inventiveness) to the Patent Office. Conversely, European Patent Office and most other jurisdictions worldwide have more lenient disclosure requirements. Prioritizing the US and Israel simplifies examination by avoiding the need to disclose citations from other jurisdictions (e.g. Europe) in the US and Israel.

The significance of disclosure in the US and Israel was highlighted in a recent Israeli Supreme Court decision that Applicants only need to disclose material documents to the Israeli Patent Office.[2] A material document is a document that, if disclosed, would cause the Patent Office to reject the patent application.

The Israeli Supreme Court decision noted the Israeli materiality requirement’s similarity with the US Therasense standard[3]. The Therasense standard requires both materiality and intent to deceive the Patent Office for a finding of inequitable conduct. However, contrary to the US standard, the Israeli Supreme Court ruled that an Applicant can be liable under competition (anti-trust) law if it intentionally tried to deceive the Patent Office to retain a monopoly unjustly.

The materiality requirement may be more significant in Israel than in the US. This is because the materiality requirement softens Israel’s broader disclosure requirement, which can require the disclosure of all documents relied on by foreign patent offices. This requirement extends beyond cited publication and can include other documents, such as arguments made in an opposition. Conversely, the US disclosure requirement is more narrowly focused on prior art publications.

Although the US and Israel acknowledge a non-materiality exemption to the disclosure requirement, utilizing the exemption in practice can be risky. Accordingly, best practice in Israel (under both the patent and competition law) and the US is for Applicants to disclose all potentially relevant information. Non-disclosure risks the potential for a later Patent Office or Court finding that the non-disclosed information was misclassified as immaterial and potentially a finding that the Applicant intentionally misclassified the material to mislead the Patent Office.

In contrast with the US and Israel, the European Patent Office has a relatively weaker disclosure requirement. The European Patent Office only requires disclosure of searches undertaken by other smaller Patent Offices before filing a European Patent Application and documents specifically requested by a European examiner. Most patent offices around the world have disclosure requirements that are similar to those of European offices. Therefore, prosecuting patent applications in Europe and other jurisdictions (e.g., China, Japan) under regular examination after the grant of the US and Israeli patents is often preferable for Israeli startups. This prioritizes swift examination in the US and Israel and avoids the need to disclose citations found in European (or other) examinations to the US and Israeli Patent Offices.

To sum up, the speed of obtaining patent protection and duty of disclosure requirements often means that startups should prioritize obtaining a US patent under track one and then an Israeli patent under accelerated examination. After obtaining protection in both the US and Israel, other jurisdictions (e.g. Europe, China, Japan) should be considered based on the startup’s needs (e.g. market, competitors).

[1] One year after a provisional application (either in tandem or following the US application), the startup inventors can file a PCT application. The PCT application allows inventors to obtain patent protection in virtually all jurisdictions worldwide. The PCT application postpones the decision as to whether to file a patent application in a particular jurisdiction for at least 30 months after a provisional application is filed.

[2] DNA 5679-21 Sanofi v. Unipharm (December 2023)

[3] Therasense, Inc. v. Becton, Dickinson & Co., 649 F.3d 1276, 99 U.S.P.Q.2D (BNA) 1065 (Fed. Cir. May 25, 2011)